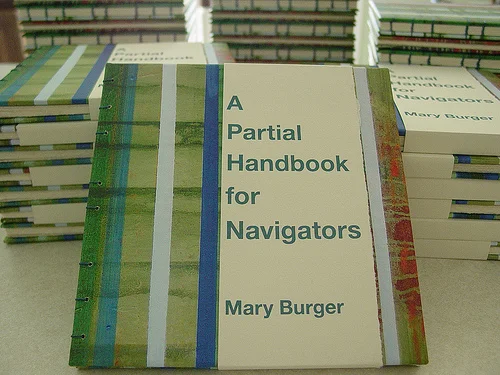

A Partial Handbook for Navigators

Writings on relationship to place.

Interbirth Books, 2008

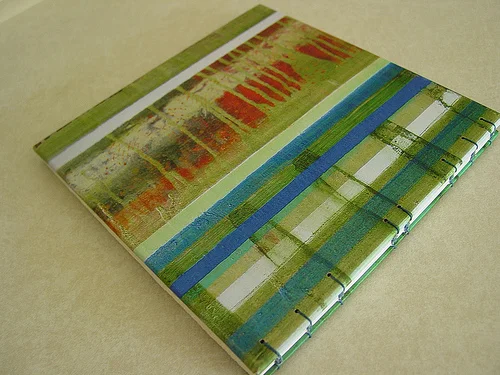

One hundred books were hand bound using a traditional Coptic stitch, with cover art by Amy Trachtenberg: Rift Zone, 2008.

"Although there are echoes of the essay, the serial poem, page-as-canvas spatial arrangements, memoir, and pose poetry, Burger sculpts and grafts these various divergent approaches into a new kind of writing, one which at its core is concerned with the exploration of ambulatory forms, with our false perceptions of stasis, and with momentary and mountainous delineations of time."

—Noah Eli Gordon

Notes From the Ground

from A Partial Handbook for Navigators

It’s nothing like being dead.

I made an early-morning trip to lie in a shallow grave and watch the Golden Gate Bridge emerging from the fog. Karl and his friends placed shovels of dirt on me. He said tell him if it got hard to breathe.

It was workaday city dirt, gray, clumpy, littered with human detritus. No fragrant humus, no romance of fertility and renewal.

Karl and the rest drifted away to leave me alone with my interment. The weight of the soil pressed lightly, my head lolled on its earth pillow. I was immobilized, more by my complicity than by the weight itself. My hands at my sides, I was released from activity.

At grass-eye level, I flipped quickly through Horton hearing a Who, Gulliver stumbling over Lilliput. There were small things walking around down there. My point of view on the ground plane made knee-jerk reactions irrelevant. I stared at the Golden Gate, impressed by my private audience. A pelican flew low overhead, its usually-inaudible wing beats amplified. The perimeter revolved with joggers, dog walkers, early strollers. What would I tell them if any asked why I was lying here at seven in the morning with only my head above ground?

I went into the earth to find out if it was any different there.

I went looking for some recognition on the earth’s part, or my part, that we were together.

I find cemeteries especially interesting because they represent both the beginning and the end of landscape and architecture. Architectural historians are in common agreement that the tomb represents the very first attempt to create enduring built structures. –Ken Warpole

This structure was not a tomb and not enduring, not really a structure. Park caretakers would restore the sod after we left.

In early Europe and America, the dead were placed in small churchyards in bustling town centers, with austere slab headstones and no greenery to distract from the somber business of mourning. By the nineteenth century, the rise of Enlightenment secularism combined with a new public aversion to living near corpses and a growing romanticist taste for picturesque landscapes. A modern hybrid emerged: the rural cemetery. In these park-like settings, graves were arranged beneath groves of trees, and the leafy paths and vistas were designed as much for the pleasures of the living as for the remembrance of the dead. Families might take an excursion to the edge of the city, pay their respects to a forbear, and enjoy a picnic under the elms. The first of these destination cemeteries, Pere-lachaise, opened on the edge of Paris in 1803. Variations arose across the United States, from Mount Auburn near Cambridge to Mountain View in the Oakland hills. These early memorial/recreational sites organized the emotions in rambling but decorous arrays. White marble monuments in ancient Greek, Roman, or Egyptian style perched among landscapes designed for poetic, transcendental contemplation. As years went on, plantings became more ornamental, and the cemeteries came to resemble arboreta.

But within a century, it seems, the miniature cities of monuments and carefully framed views had become too sumptuous to encompass contemporary understandings of mortality, or of land use. Twentieth-century cemeteries began to emphasize utility and regularity, with little investment in design. Yet one among them stands out.

The Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm, begun in 1915, restored the use of simple slab headstones but scattered them among deep forest, with broad grassy slopes beyond. It was as if the churchyard cemetery were sprung from its pen and released into the countryside. The interspersing of natural landforms and modest stone markers evokes layered responses; here, we who’ve been born in the past hundred years or so can recognize some of the complexity of our mortal predicament. Swedish landscape architect Thorbjörn Andersson describes the effect as “feelings of landscapes of many different sorts, such as hope and happiness, sorrow and despair, death and resurrection. It is an environment full of feelings that facilitate contact between the inner and outer landscapes.”

Part disappearing act, part self-amplification.

My moment was nothing like death.

Rod’s father died the day before. It wasn’t unexpected. It wasn’t tragic. It was an end of a definite kind. He met me at Crissy Field after my voluntary interment to take a walk before he flew east for the funeral.

Everything is not a metaphor for everything.

It was nothing like being dead, but the comparison with a gravesite was inevitable. If this were to be my grave some day—this over-famous site that had been my youthful pilgrimage, the place where I became most alive—I would not live to regret it.